Evolutionary Computation

Life is hard. The environment is full of dangers and it is constantly changing. Yet it is full of living organisms which successfully inhabit this planet for billions of years. Each individual living being is a survival expert in their particular domain. For example, the arctic rabbit is a survival expert in the domain of northern Canada. With a little bit of imagination, we can consider each individual arctic rabbit to be nature's solution to the mathematical problem of constructing a living machine capable of surviving in the arctic. Looking at how successful nature is in creating complicated solutions such as the arctic rabbit, humans tried to imitate evolution to solve mathematical problems.

Evolution works on two levels, the genetic level, and the environmental level. On each level, there are two fundamental concepts: mating and survival of the fittest at the environmental level, and crossover and mutation on the genetic level.

In a population of rabbits, there is always competition for mating. Female rabbits prefer partners, whom they consider strong and fit. One way the female rabbits possibly do this is by looking at the white fluffy tails for signs of diarrhea.1 Rabbits with better genes, who have stronger immunity systems, have a smaller chance to contract diarrhea, and hence a higher chance to be chosen by the females for mating. Therefore ''better genes'' have a higher chance to proliferate.

When rabbits mate, their DNA is recombined using crossover to create the DNA of a brand new rabbit. The baby rabbit gets some proportion of his genetic code from his father and some from his mother. This way, he may inherit some good or bad traits from his parents. In addition, his DNA is altered a little by random errors in the DNA replication process. The introduction of these errors is called mutation. However, in this article I want to concentrate mainly on crossover.

Once a baby rabbit is born, he has to prove himself, by surviving in the harsh environment. If the offspring rabbit inherited bad genes from his parents, he will have a smaller chance of surviving until maturity and a smaller chance to reproduce and pass these bad genes on. On the other hand, if he inherited good genes, he has a higher chance to have many children himself, and to proliferate his genes further.

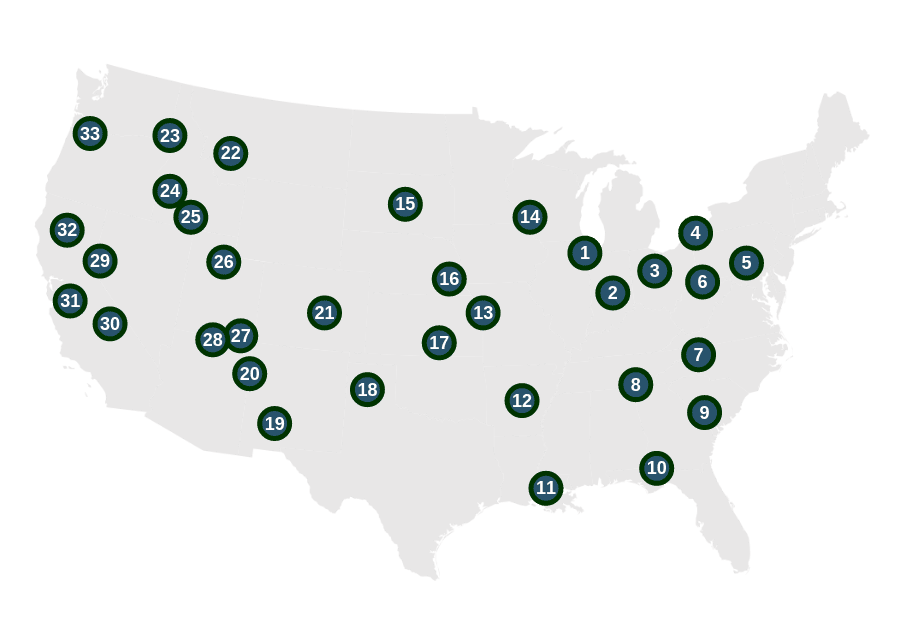

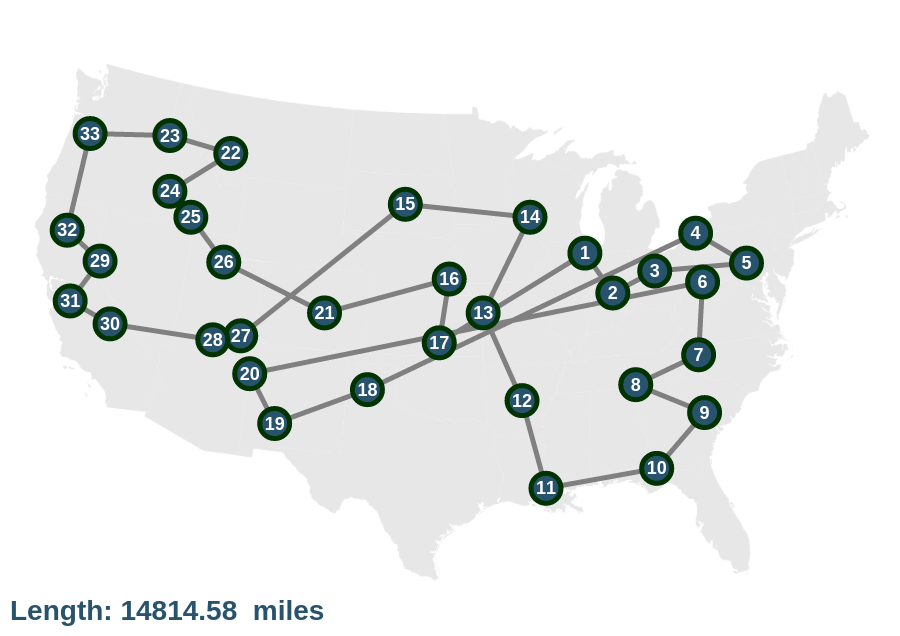

Now let us look at how we can use the ideas of evolution in the task of finding the best round trip through the 33 cities. First of all, we need DNA. That is, we need some concise way on how to encode a solution to the road trip problem. One possible way is to give each city a number like this:

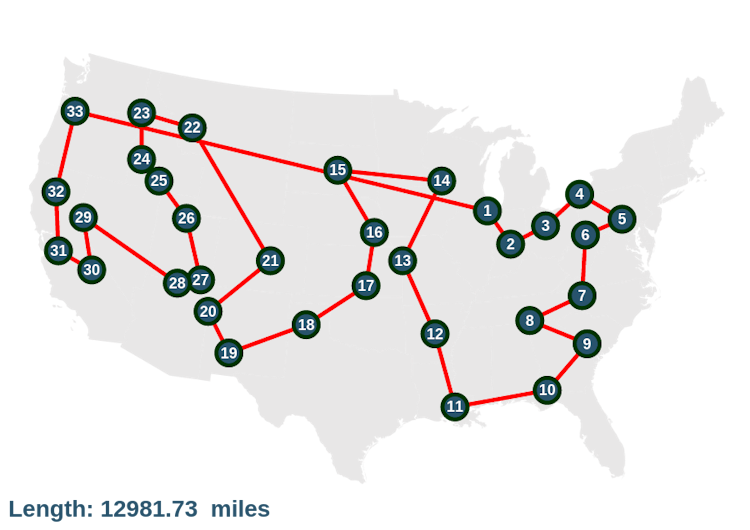

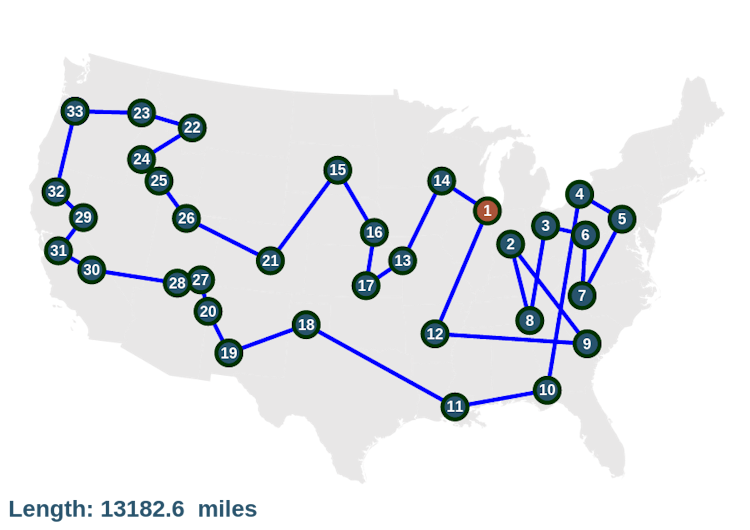

Then each road trip can be represented as a sequence of numbers 1 to 33. Now that we have a genetic representation, we can manipulate the individual road trips in interesting ways. Let us take 2 random road trips, one illustrated in blue, and one in red.

Each trip has its own genome, which is illustrated in the picture bellow. Now let us suppose that these two road trips are going to mate, to create children. We need some way in which to combine the red genome and the blue one, so that we get a valid genome of some other road trip around all the cities. For example, we do not want to visit one city twice. Similarly, when constructing rabbits, nature ensures that the resulting rabbit does not have two tails.

One way to do it for the road trip problem is the so-called order crossover.2 The procedure is illustrated in the image above. At first, an arbitrary block of symbols is inherited from the first parent (the red genome). Next, symbols are inherited one by one from the second parent, but only if they are not already present in the offspring. This ensures that each symbol is present in the offspring exactly once. Once the genome of the offspring is generated, we can construct the round trip corresponding to this genome:

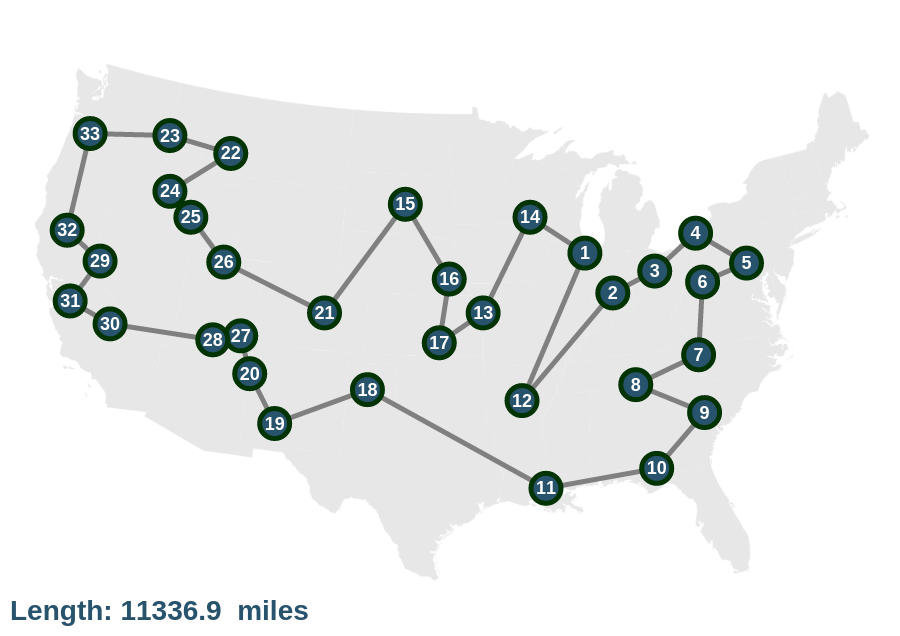

Here we see a remarkable thing. The offspring has a shorter length than both of its parents! Looking at the image closely, we see the reason behind this. The blue parent makes a lot of unnecessary trips in the east (right) part of the map. The offspring however does not inherit this faulty sequence, but instead inherits the eastern part of the trip from the red parent, who performs quite well on this part of the map. Conversely, the red parent stumbles in the western part of the map, but the offspring inherits the western part from the blue parent, who fares very well. However, an offspring does not necessarily inherit the good traits of its parents. If the block inherited from the red parent was a little different, such as in the following picture:

The resulting offspring would still inherit the good western part from the red parent and the good eastern part from the blue parent, but in a way that would combine them very clumsily. We can see this in the following picture.

This is where the survival of the fittest comes into play. Let us suppose that we began with 100 randomly generated genomes and by mating we generated 100 more. Now, we have 200 individuals. Each producing a round trip of a different length. What we usually do at this point is to pick the worst 100 individuals, that is 100 individuals producing longest round trip, and to delete them from the population. This way we ensure that bad gene sequences do not propagate further.